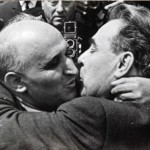

To understand these positions, we have to examine the narratives that lie behind them. Ruska Filova repeats the narrative she learnt at school in the 1970s. Bulgaria – the oldest civilization in the world – was doomed to fall under the “Ottoman yoke” for 500 horrible years. They were rescued from barbaric slavery and “genocide” by the heroic self-sacrifice of the Russians. And in 1944, Russia again had to step in to rescue Bulgaria from an oppressive pro German “fascist” government and usher in a period of socialist stability with jobs for all, free health care and education, and pensions that guaranteed dignity in old age. Imprinted on her memory is the poster of Brezhnev clasping the Bulgarian premier Zhivkov in his arms

and the slogan Eternal Comradeship from century to century. (Or at least up to Zhivkov’s fall in 1989)

and the slogan Eternal Comradeship from century to century. (Or at least up to Zhivkov’s fall in 1989)This narrative then helps form Ruska’s explanation of events following 1989. First the malignant west with the help of the “traitor” Gorbachov finally succeeded in undermining the Communist bastion. Then a succession of corrupt “democratic” politicians and criminal oligarchs, interested only in filling their pockets, destroyed the Bulgarian economy. As a result of closing factories, the nation is being fatally weakened by the mass emigration of the young and most talented. Meanwhile the west continues to exert its malign influence. Bulgarian Orthodox culture is under constant attack from NGOs espousing “western values” of multi-culturalism, gay rights etc. Bulgaria was sleepwalked into NATO and the EU, organizations that are intent on completing Bulgaria’s destruction. Attacks on the traditional Bulgarian family means that it is only a matter of time before gypsy and Muslim populations become the majority. The CIA dream of a friendly Muslim power stretching from Diyarbakir to Tirana will have been realised.

Ruska Filova is keen to remind us that from the Crusades onwards the West has always been anti-Bulgarian. In the 1870s, the western powers supported the Ottoman Empire in their “genocidal” oppression. Some of her friends go so far as to suggest an infernal Jewish conspiracy, linking Disraeli with Suleiman Pasha, the perpetrator of the Stara Zagora massacre. On the anniversaries of the April revolution and the Battle of Shipka, Ruska posts that the Ottoman Bashibazouks represent “western values”. For her “western values” are unchanging through the centuries and are essentially hostile.

This special hatred for Bulgaria applies to more recent events, particularly the Treaty of Neuilly following the end of the WW1. Then the Allied bombing of Bulgaria during the Second World War is denounced as a war crime and explained by Churchill’s legendary “hatred” of Bulgaria. Some of Ruska’s friends, who while being pro Putin do not share her enthusiasm for communism, blame Churchill for allowing Stalin to take over Bulgaria.

It comes as no surprise then that for Ruska, Vladimir Putin is a hero and she readily reflects the Putin view of the world. She is horrified that Bulgarian politicians have showed such ingratitude to Russia by joining the anti-Russian NATO and that as a result Bulgaria will be dragged into World War 3 on the wrong side. (Even the “fascist” Tsar Boris did not allow Bulgarian soldiers to fight against Russia.) She applauds Putin’s bold stand against western influences. She points out that with his fearless involvement in Syria once again Russia will save Europe from the barbarians. She holds Western meddling entirely responsible for every crisis in the world – she will offer facts to prove that American provocateurs were responsible for the unrest in Ukraine. She will post pictures of the eviscerated bodies of East Ukrainian children and accuse the western press of hypocrisy in ignoring the “war crimes” of Ukraine’s “fascist” government.

On the other hand, Rilka Russofobska routinely describes Ruska and her friends as brainwashed red rubbish. Of course she has a different set of facts and this forms a new narrative, which directly contradicts most of what she and Ruska learnt at school. For her the outstanding catastrophe in Bulgaria’s history (far worse than either the Ottoman “presence” or the WW1 settlement) was the illegal invasion by the Soviet Union in 1944 and the subsequent imposition of an alien communist system that resulted in the extermination of Bulgaria’s intellectual and entrepreneur class and the demolition of a thriving agricultural and industrial economy.

Rilka even questions whether Russia has ever been a true friend of Bulgaria. Didn’t the Russian invasion in the tenth century lead to the fall of the first Bulgarian kingdom? Wasn’t the Russian Tsar’s “liberation” of Bulgaria just a move to gain Russian access to the Mediterranean? Great figures from Bulgarian history, Rakovski, Levski, Botev and Stambolov had all forewarned the Bulgarian people of the dangers of the anti-democratic Russian bear. Rilka is fond of repeating the story of the oppressed Russian peasants in the Tsar’s army in 1887, how they were amazed at the freedom and prosperity of their Bulgarian counterparts. And the Russians proved to be capricious. In the years following 1878 Russia shifted its friendship first to Serbia and then to Yugoslavia, thus preventing Bulgarians’ desire to re-unite with their “brother Macedonians”.

Despite the catastrophe of WW1 Rilka puts a positive gloss on Bulgaria between the wars. She vehemently denies that Bulgaria was ever a Fascist society and praises the statesmanship of Tsar Boris III. She paints a golden picture of selfless politicians and civically minded Generals, steering a principled path despite Communist terrorists and peasant demagogy. Why then did the Tsar ally himself with Hitler? Rilka maintains it was because he had no choice. In the deteriorating Balkan situation, with Germany in the ascendant he had to put the safety and interests of Bulgaria first. But he was no pawn in Hitler’s hands. He refused to declare war on Russia, in spite of Russia’s murderous terrorist campaign. Rilka goes on to insist that it was down to Tsar Boris alone that Bulgaria’s Jewish population were not dispatched to Nazi extermination camps. This has led to some memory conflicts with prominent Jewish writers. Facts are exchanged like machine gun bullets.

Jumping to the present day, how does Rilka explain the current state of Bulgaria to her former classmate Ruska? Well of course it’s the Communists to blame. Those far-sighted scoundrels had foreseen the fall of the Berlin Wall and had infiltrated every so called opposition party, so that whoever won the elections, Bulgaria would be asset stripped for the benefit of Communist children and grandchildren. Rilka also blames the Bulgarian people for being so easily hoodwinked particularly by demagogues and pseudo-patriots.

She is alarmed at the rise in Vladimir Putin’s popularity. She calls Putin Putler and adorns his photo with a moustache. She periodically laments the weakness of the west’s response. Her heroes are Ronald Reagan and Maggie Thatcher.

Of course Rilka and Ruska are extreme stereotypes, but their debate on Facebook involves a thousand divided voices, each accusing the other of being in the pay of the CIA or the KGB. Meanwhile, as one of my more neutral ex-pupils pointed out, Bulgaria is 75% Russophile yet it continues to vote for moderately Russophobe politicians. ]]>

Last month an extremely talented young writer with an inestimable future died when the car in which she was traveling hit a wall of water, on the cruelly deceptive Sofia Burgas motorway.

Last month an extremely talented young writer with an inestimable future died when the car in which she was traveling hit a wall of water, on the cruelly deceptive Sofia Burgas motorway.